|

|

West 11

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd February 2015). |

|

The Film

West 11 (Michael Winner, 1963) West 11 (Michael Winner, 1963)

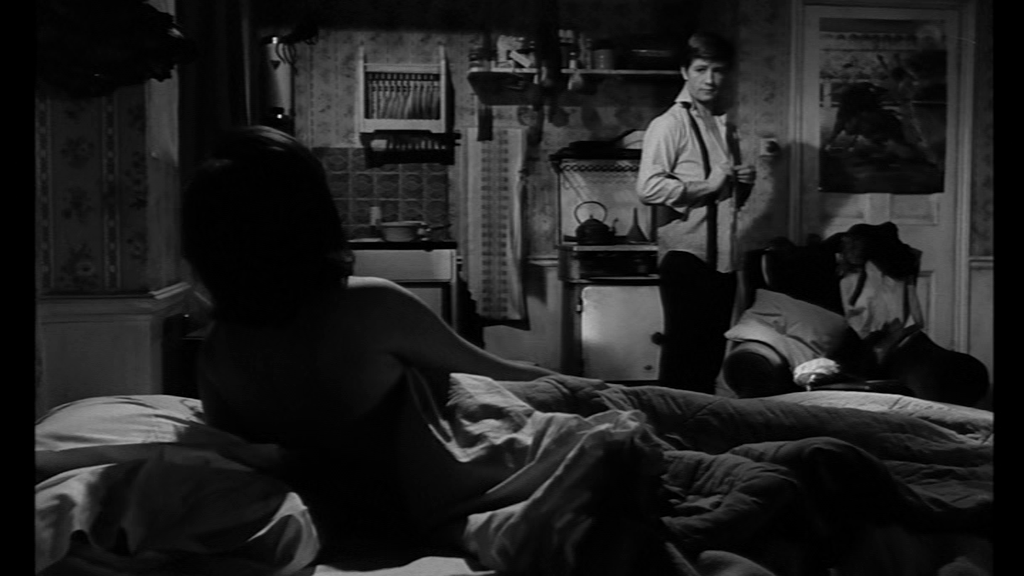

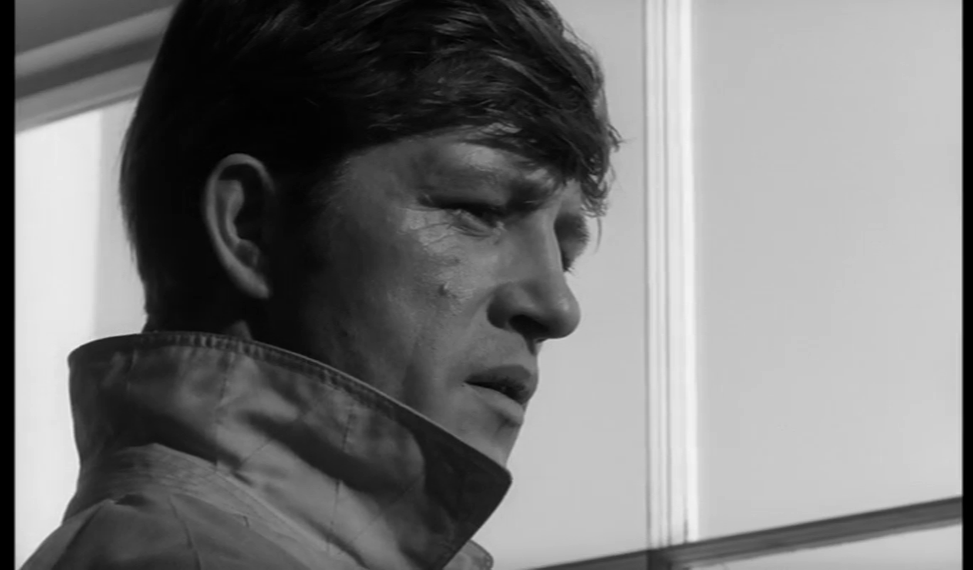

Throughout the 1960s – prior to his work in Hollywood, and his association with the cinema of exploitation, with films like Death Wish (1974), The Mechanic (1972) and the superb Westerns Lawman (1971) and Chato’s Land (1972) – Michael Winner’s work as a director displayed a tendency to oscillate between comedies such as Play it Cool (1962) and You Must Be Joking (1965) and ‘kitchen sink’-style dramas, with an element of social realism, like West 11 (1963) and I’ll Never Forget What’s’isname (1967). West 11 focuses on a young man, Joe Beckett (Alfred Lynch). Joe is first encountered leaving the bed of a young woman, Ilsa (Kathleen Breck). He returns to his own home, a dreary bedsit on West 11, Notting Hill Gate, for which he pays £2 10s per week. He works in a tailor’s shop but is continually late for work. After a confrontation with his manager, Joe hands in his notice. However, Joe is spotted by another customer, ‘Captain’ Richard Dyce (Eric Portman). Dyce follows Joe and engineers a meeting with him in a café. Telling Joe that ‘You haven’t got the guts to seize life by the throat and take what you want’, Dyce persuades Joe to allow Dyce to accompany him to a party, where Joe flirts with older divorcee Georgia (Diana Dors), much to the chagrin of Ilsa, who is also at the party. (‘Isn’t she out of your age group, old boy?’, Dyce asks Joe, in relation to Georgia. ‘I’m not fussy’, Joe responds.) Dyce leaves the party with Georgia. The next day, Dyce leaves Georgia and, telling Georgia he is on his way to a business meeting, meets with his aunt; his status as a con artist and a compulsive liar is seemingly confirmed when he tells his aunt about his ‘thriving’ business, but she responds by simply declaring, ‘Dickie, you get more ridiculous every day’. Meanwhile, Dyce has one of his associates follow Joe. After passing through an anti-immigration rally by the Britain First Party, which subtly underscores gives a wider context for the film’s narrative by highlighting the tensions within London, Joe encounters Dyce in a dingy café. There, after Joe has told him ‘Never mind that bloody Oscar Wilde patter’, Dyce cuts to the chase, offering Joe a job of work: ‘How would you like to work me? [….] How would you like to make £10,000?’ Dyce’s plan involves Joe breaking into Dyce’s aunt’s house and killing her, thus enabling Dyce to collect his inheritance: ‘We’ve all got to go, sooner or later’, Dyce tells Joe, adding, ‘Has it never occurred to you that the only perfect crime is when one stranger murders another?’ Joe refuses Dyce’s proposition.  Joe discovers that Ilsa is in love with someone else. The ensuant fight draws the attention of Joe’s landlady, who ejects Joe from his bedsit. Outside, now homeless, Joe saves an elderly neighbour, Mr Cash (Finlay Currie), from being tormented by three young thugs (including a very young David Hemmings). Joe strikes up a friendship with Cash, who reveals that he left behind a conventional middle-class life for an almost monastic existence in a bedsit surrounded by books. After the death of Joe’s mother casts Joe even further adrift in the existential void of life, Joe accepts Dyce’s proposition and agrees to kill Dyce’s aunt (‘It’s like war, boy: it’s adventure’, Dyce tells him). Meanwhile, Ilsa becomes concerned for Joe’s welfare, deduces Joe’s involvement in Dyce’s criminal plan, and attempts to track Joe down. Joe discovers that Ilsa is in love with someone else. The ensuant fight draws the attention of Joe’s landlady, who ejects Joe from his bedsit. Outside, now homeless, Joe saves an elderly neighbour, Mr Cash (Finlay Currie), from being tormented by three young thugs (including a very young David Hemmings). Joe strikes up a friendship with Cash, who reveals that he left behind a conventional middle-class life for an almost monastic existence in a bedsit surrounded by books. After the death of Joe’s mother casts Joe even further adrift in the existential void of life, Joe accepts Dyce’s proposition and agrees to kill Dyce’s aunt (‘It’s like war, boy: it’s adventure’, Dyce tells him). Meanwhile, Ilsa becomes concerned for Joe’s welfare, deduces Joe’s involvement in Dyce’s criminal plan, and attempts to track Joe down.

West 11 was based on a novel by Laura Del Rivo, entitled The Furnished Room, that Michael Winner described in his autobiography as ‘about misfits in early sixties Notting Hill Gate, then full of seedy bed-sitting rooms’ (Winner, 2005: 83). The adaptation was scripted by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall: the film was produced a year after Waterhouse and Hall’s adaptation of Stan Barstow’s A Kind of Loving, directed by John Schlesinger, and the same year as Schlesinger’s big screen adaptation of Waterhouse’s novel Billy Liar. Originally, Winner claims, the film’s producer Danny Angel offered the film to Joseph Losey to direct, and intended for it to star Warren Beatty and Claudia Cardinale: ‘What Warren Beatty would have been doing in a bed-sit in Notting Hill Gate I can’t imagine!’, Winner quips in Winner Takes All: A Life of Sorts (ibid.). Angel offered the film to Winner instead, and Winner felt that the picture ‘gave me a chance to direct a “real” film even though the script and book were downbeat and unlikely to be commercial’ (ibid.).  For the role of Ilsa, Winner claims, three young actresses were tested: Julie Christie, Suzanne Farmer (‘who was in Hammer Horror films and had very large bosoms’, Winner informs us) and Kathleen Breck (ibid.). Although Winner pushed for Julie Christie to be given the part, he claims that Danny Angel called her ‘a B-picture actress’, adding that ‘Everybody knows she’ll never get anywhere’ – reflecting on the rejections Christie had been met with when she tested for Clive Donner’s Nothing But the Best (1964) and Schlesinger’s Billy Liar (the part in the latter film eventually went to Christie when the first choice for the role, Topsy Jane, fell ill) (ibid.: 84). Winner reflects on a bizarre exchange which followed, in which Angel asked him, ‘‘Who’d want to fuck Julie Christie?” I said, “I would!” Danny responded, “Well, you’re a homosexual!’ (ibid.). This, Winner tells us, ‘was a typical Danny Angel exchange’ because ‘He knew I wasn’t a homosexual’ (ibid.). Having put Winner in his place, Angel railroaded everybody into giving the part to Kathleen Breck. For the role of Ilsa, Winner claims, three young actresses were tested: Julie Christie, Suzanne Farmer (‘who was in Hammer Horror films and had very large bosoms’, Winner informs us) and Kathleen Breck (ibid.). Although Winner pushed for Julie Christie to be given the part, he claims that Danny Angel called her ‘a B-picture actress’, adding that ‘Everybody knows she’ll never get anywhere’ – reflecting on the rejections Christie had been met with when she tested for Clive Donner’s Nothing But the Best (1964) and Schlesinger’s Billy Liar (the part in the latter film eventually went to Christie when the first choice for the role, Topsy Jane, fell ill) (ibid.: 84). Winner reflects on a bizarre exchange which followed, in which Angel asked him, ‘‘Who’d want to fuck Julie Christie?” I said, “I would!” Danny responded, “Well, you’re a homosexual!’ (ibid.). This, Winner tells us, ‘was a typical Danny Angel exchange’ because ‘He knew I wasn’t a homosexual’ (ibid.). Having put Winner in his place, Angel railroaded everybody into giving the part to Kathleen Breck.

The male lead was originally intended to be played by Sean Connery; but again, Winner claims, Angel dismissed Connery as ‘Another B-picture actor! No one will ever be interested in Sean Connery’ (ibid.). Oliver Reed was also considered for the lead role in West 11, but Angel once again dismissed him: Reed later declared that ‘Danny Angel said Christie was a B-picture artist and I was a nothing—but Danny Angel couldn’t walk, so I couldn’t knock him over’ (Reed, quoted in Meikle, 1996: 150; emphasis in original). Angel similarly dismissed James Mason, who was interested in playing Dyce, as a ‘has-been’ (Winner, op cit.: 85). So instead ‘of a film with Julie Christie, Sean Connery and James Mason’ we ended up with ‘Alfred Lynch, Kathleen Breck and Eric Portman’ (ibid.). However, Winner relished the opportunity to direct a number of other actors in smaller parts, including Diana Dors, Patrick Wymark, Kathleen Harrison, Francesca Annis and David Hemmings. Winner wanted to inject a level of realism into the film by shooting it largely on location, in the manner of French New Wave cinema or Italian Neo-Realism. However, Angel resisted this, declaring ‘We don’t want a lot of wobbly cameras like they have in the French New Wave. In England we make films in studios’ (ibid.). Angel also struggled to comprehend Winner’s approach to shooting, which avoided using master shots and instead focused on picking up shots in ‘little bits that needed to be joined together’ (ibid.). During the production of Lawman, Robert Ryan reputedly compared Winner’s way of shooting to that of John Ford (ibid.: 86). Winner’s approach, he claims, ‘is better for the actors’ as it avoids the necessity of making them ‘say the same lines endlessly throughout the day’ and also means that ‘if you want to change anything you’re not stuck to the master shot. You can adapt your shooting and dialogue as you go along’ (ibid.).  From Joe’s first frustrated assertion, in the opening sequence, that Ilsa is not-so-secretly conducting a relationship with another man, and her refusal to commit to Joe, to his early humiliation at work (‘And we don’t wear coloured shirts to work, Mr Beckett, whatever we may do outside’, his manager tells him), the audience is forced into a position of sympathy with Joe. When a customer enters the tailor’s shop and requests a simple raincoat, Joe tells the man truthfully that the shop doesn’t carry his size in stock. However, when the customer leaves the shop Joe is chastised by his manager for not trying to sell the customer an overcoat instead. ‘The man came in for a raincoat off the peg. We haven’t got one’, Joe tells his manager matter-of-factly. ‘What are we, Mr Beckett?’, the manager asks, ‘Salesmen! Salesmen! There’s no such word as “haven’t got”’. From Joe’s first frustrated assertion, in the opening sequence, that Ilsa is not-so-secretly conducting a relationship with another man, and her refusal to commit to Joe, to his early humiliation at work (‘And we don’t wear coloured shirts to work, Mr Beckett, whatever we may do outside’, his manager tells him), the audience is forced into a position of sympathy with Joe. When a customer enters the tailor’s shop and requests a simple raincoat, Joe tells the man truthfully that the shop doesn’t carry his size in stock. However, when the customer leaves the shop Joe is chastised by his manager for not trying to sell the customer an overcoat instead. ‘The man came in for a raincoat off the peg. We haven’t got one’, Joe tells his manager matter-of-factly. ‘What are we, Mr Beckett?’, the manager asks, ‘Salesmen! Salesmen! There’s no such word as “haven’t got”’.

From the outset, Joe’s relationship with Ilsa is riddled with jealousy; a conflicted young woman, Ilsa seems committed to the idea of non-commitment, resistant to the concept of monogamy, and aware of her burgeoning sexual power. When Joe encounters her at the party to which he has brought Dyce, Ilsa dances in front of a crowd of men, clearly enjoying the attention, before chastising one of the men bitterly for looking at her legs. In the opening sequence, when we first see Joe and Ilsa in her bedsit, they are involved in a post-coital argument. ‘I wasn’t there’, Ilsa protests. ‘You were there’, Joe responds: Ilsa was in Tony’s club ‘with a man’, he says, ‘the same man you were out with last week’. Ilsa is a confused girl who is willing to exploit her own sexuality and ‘play the field’ in a manner that, stereotypically, is associated with men. Her moment of lucidity comes when she tells Joe, ‘I enjoy making a man fall in love with me, especially if he doesn’t want to. Then when I’ve got him, I go off him. I can’t stand dog-like devotion’. However, in the same sequence, as soon as she is in Joe’s bed, she demands, ‘Keep me safe, Joe. Love me and look after me’. When her declaration to Joe that she is in love with someone else results in Joe becoming angry (‘You’re just a complete tart, aren’t you? [….] You bloody little scrubber! You bloody little slut!’), Ilsa pathetically underscores her need for positive male attention, telling him weepily, ‘Don’t be angry with me, Joe. Nobody must be angry with me. Everybody must love me’. Joe’s life is characterised by emptiness and a lack of meaning. During their first encounter, Dyce asks Joe, ‘Do you really enjoy working in shops?’ ‘Well, what jobs are there?’, Joe queries in response, ‘I’ve tried a few I thought I’d like but they’re no good when you get close to them. Now, I pick lousy jobs deliberately. If I found a good one, I’d probably stay in it and settle down. That would just about be the end’. Dyce’s response to this subtly highlights his misogyny/misanthropy, which goes unnoticed and unchecked by Joe: ‘I know what you mean. End up at fifty in a suburban semi, married to some fat old slag and a gang of snotty-nosed infants’.  However, Joe soon finds that the people around him are also living lives of quiet desperation, and discovers facts about them that challenge the stereotypes he holds. He discovers that the apparently confident, sexually predatory Georgia is in fact a divorcee who has a young daughter; her child is being raised by Georgia’s parents. ‘God, I look old’, Georgia mutters in private, the mask of confidence she wears in public slipping. ‘You don’t look old, love’, Joe reassures her. ‘Old enough to want another husband; not young enough to get the kind I want’, Georgia tells him. Meanwhile, Cash informs Joe that at Joe’s age, he ‘had everything’, including a family and a comfortable home, but cast it all aside to search for ‘the truth’: a lonely, elderly man, Cash lives alone in a dingy bedsit, books piled from floor to ceiling. Cash asks Joe to help him plow through his books in search of ‘the truth’, stating that now Joe has been rendered homeless and his relationship with Ilsa has collapsed, Joe and Cash are alike. However, Joe is alienated by the elderly man’s delusions: it’s a moment that is underscored by the camera moving away from the pair to frame them in a high-angle long shot that acts as a metaphor for how small these two lonely men are – even in Cash’s tiny bedsit. However, Joe soon finds that the people around him are also living lives of quiet desperation, and discovers facts about them that challenge the stereotypes he holds. He discovers that the apparently confident, sexually predatory Georgia is in fact a divorcee who has a young daughter; her child is being raised by Georgia’s parents. ‘God, I look old’, Georgia mutters in private, the mask of confidence she wears in public slipping. ‘You don’t look old, love’, Joe reassures her. ‘Old enough to want another husband; not young enough to get the kind I want’, Georgia tells him. Meanwhile, Cash informs Joe that at Joe’s age, he ‘had everything’, including a family and a comfortable home, but cast it all aside to search for ‘the truth’: a lonely, elderly man, Cash lives alone in a dingy bedsit, books piled from floor to ceiling. Cash asks Joe to help him plow through his books in search of ‘the truth’, stating that now Joe has been rendered homeless and his relationship with Ilsa has collapsed, Joe and Cash are alike. However, Joe is alienated by the elderly man’s delusions: it’s a moment that is underscored by the camera moving away from the pair to frame them in a high-angle long shot that acts as a metaphor for how small these two lonely men are – even in Cash’s tiny bedsit.

Through these events, Joe undergoes a personal crisis which results in him accepting Dyce’s proposition. Unable to find satisfaction or fulfillment either in his work or in his relationship with Ilsa, he concludes that ‘I’m an emotional leper. I don’t feel anything. I try to but I can’t. I’ve got no sense of touch [….] Work, women, everything’. He begins to consider Dyce’s proposal, expressing his anxieties about his life in a way that is almost Sartrean, highlighting the associations between the ‘angry young man’ movement in British literature and drama and continental post-war existentialism: ‘Suppose a man has grown up with certain beliefs and values’, Joe tells Cash, ‘Then he loses them all. They just slip away. Then there’s no meaning in life. There’s no point [….] Unless he finds he can put his own meaning in life. If he wants to live for pleasure, he can do; if he wants to commit a crime, he can do’. Having already reasoned that that ‘Crime can be a way of breaking out, a way of feeling something. Anything’s better than nothing’, and seeing the elderly Cash’s lonely existence as his potential future, Joe accepts the job of work offered to him by Dyce, agreeing to murder Dyce’s aunt. Joe’s mother (Kathleen Harrison) offers a caring, stabilising presence in Joe’s life, but her values are resisted by Joe. She visits him in his dingy bedsit, forcing Joe to rush Ilsa out of his bed so as to avoid his mother’s disapproval. Whilst out in a park, near a children’s playground, Mrs Beckett asks Joe, ‘You will get married one day, won’t you, Joe?’, and goes on to question his lifestyle. Her comments are inherently conservative but are framed sympathetically: ‘All these ideas about not marrying and “free love”, or whatever you call it… They’re all right in books, but there’s nothing “free” about behaving like an alley cat’, she says, ‘You want a girl you can respect, not someone who lets you paw her about; because she’ll let other fellas paw her about too’. Unknowingly painting a picture of Joe’s potential future that compares him with Dyce, Mrs Beckett warns Joe that ‘You’ll finish up one of these dirty old men, going around nipping young girl’s bottoms’. (Mrs Beckett’s words of advice are echoed by a Catholic priest with whom Joe converses, who warns Joe that ‘The city is full of dangers: bad companions, young girls with no moral upbringing’.)  Although Joe’s mother plays a significant role in the narrative, Joe’s father is conspicuously absent from his adult life, presumably dead. Cash and Dyce, both of whose lifestyles seem to hint at what may be in store for Joe in his future, symbolically fill the role of Joe’s absent father. Cash is depicted as sympathetic, helping Joe and offering him advice; but the depth of Cash’s delusions are withheld until Cash breaks the news about Mrs Beckett’s death to Joe and offers him comfort, then suggests that he and Joe are alike, and that Joe can now aid Cash in his seemingly futile search for ‘the truth’. Joe withdraws from this suggestion in horror. Meanwhile, Dyce offers another symbolic father figure for Joe. Dyce tells Joe that ‘I was taught to command. People like me give orders; people like you obey them’. Everything Dyce says is ambiguous, however: he insists that people call him ‘Captain’ Dyce, and in the sequence that introduces him, he requests the manager of the tailor’s shop show him a regimental tie. However, when asked which tie he would like, Dyce simply queries, ‘What regiments have you got?’ Although Joe’s mother plays a significant role in the narrative, Joe’s father is conspicuously absent from his adult life, presumably dead. Cash and Dyce, both of whose lifestyles seem to hint at what may be in store for Joe in his future, symbolically fill the role of Joe’s absent father. Cash is depicted as sympathetic, helping Joe and offering him advice; but the depth of Cash’s delusions are withheld until Cash breaks the news about Mrs Beckett’s death to Joe and offers him comfort, then suggests that he and Joe are alike, and that Joe can now aid Cash in his seemingly futile search for ‘the truth’. Joe withdraws from this suggestion in horror. Meanwhile, Dyce offers another symbolic father figure for Joe. Dyce tells Joe that ‘I was taught to command. People like me give orders; people like you obey them’. Everything Dyce says is ambiguous, however: he insists that people call him ‘Captain’ Dyce, and in the sequence that introduces him, he requests the manager of the tailor’s shop show him a regimental tie. However, when asked which tie he would like, Dyce simply queries, ‘What regiments have you got?’

Tony Williams has stated that Dyce’s pursuit, and his courting of Joe as the agent of the murder of Dyce’s aunt, is ‘sexually ambiguous’: after spotting Joe at work in the tailor’s, Dyce essentially stalks Joe, engineers a first meeting with him in a café, and hires one of his associates to follow Joe’s movements. (Williams, 2004: 168). In an essay about Eric Portman’s career, Williams declares that the character of Dyce ‘is a sadistic and dangerous manipulator’ (ibid.). Dyce develops a relationship with Georgia which, it is strongly suggested, is characterised by a form of abuse that is not directly confronted within the script, and he is ‘[m]ysteriously dependent on another dominant mother figure, Aunt Mildred’ (ibid.). Andrew Spicer has commented that the character of Dyce in West 11 is one of a number of roles that Portman essayed in the later years of his career which ‘were increasingly seedy and socially marginal, with the homosexual element, latent in his earlier performances, becoming more explicit’ (Spicer, 2010: 240).  Winner’s handling of the narrative is naturalistic but is also riddled with allusions. The opening shot of the film references the opening sequence of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), with its pan across the rooftops of a city (in Psycho, Phoenix, Arizona; in West 11, London), followed by a zoom in to a specific window, then a cut which takes us through the window into the room beyond, where a couple are holding a post-coital conversation. Later in the film, Winner also restages the famous shot in Psycho in which Norman/Mrs Bates (Anthony Perkins) kills the investigating detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam) and, with the camera positioned in front of his face, we see Arbogast falling backwards down the stairs. Maybe it’s down to the fact that I rewatched Mark Reichert’s Union City (1980) recently, but Ilsa’s request that Joe ‘put the milk bottle inside the door on your way out. That maniac keeps pinching it’ also seems like an offhand allusion to Cornell Woolrich’s 1937 short story ‘The Corpse Next Door’ (of which Union City is an adaptation), in which a lower middle-class man, Ed Harlan, becomes concerned that someone is stealing the milk from his doorstep; this concern develops into an obsession that leads to murder and, eventually, Harlan’s suicide. Although West 11’s setting (and the development of its narrative) is different to ‘The Corpse Next Door’, Winner’s film has a similar sense of irony and fatalism to that which characterises Cornell Woolrich’s work. Winner’s handling of the narrative is naturalistic but is also riddled with allusions. The opening shot of the film references the opening sequence of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), with its pan across the rooftops of a city (in Psycho, Phoenix, Arizona; in West 11, London), followed by a zoom in to a specific window, then a cut which takes us through the window into the room beyond, where a couple are holding a post-coital conversation. Later in the film, Winner also restages the famous shot in Psycho in which Norman/Mrs Bates (Anthony Perkins) kills the investigating detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam) and, with the camera positioned in front of his face, we see Arbogast falling backwards down the stairs. Maybe it’s down to the fact that I rewatched Mark Reichert’s Union City (1980) recently, but Ilsa’s request that Joe ‘put the milk bottle inside the door on your way out. That maniac keeps pinching it’ also seems like an offhand allusion to Cornell Woolrich’s 1937 short story ‘The Corpse Next Door’ (of which Union City is an adaptation), in which a lower middle-class man, Ed Harlan, becomes concerned that someone is stealing the milk from his doorstep; this concern develops into an obsession that leads to murder and, eventually, Harlan’s suicide. Although West 11’s setting (and the development of its narrative) is different to ‘The Corpse Next Door’, Winner’s film has a similar sense of irony and fatalism to that which characterises Cornell Woolrich’s work.

Video

West 11 is presented in 1.66:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The monochrome photography, all dingy pubs and dirty bedsits, is crisp and detailed, with excellent contrast levels – especially considering how much of the film is shot in low-light situations, with expressionistic, noir-esque lighting. The source used for the transfer is wonderfully clean, marked by a few vertical scratches here and there.

The film is presented here in the same (BBFC cut) version that was released to UK cinemas in 1963, here running 89:35 mins (with PAL speedup): UK cinema release prints ran 8364 feet (92:56 mins), with the BBFC listing the running time of the film when submitted as 94:45 mins. (Therefore, approximately two minutes of footage seems to have been cut by the BBFC in order for the film to qualify for its original ‘X’ certificate.) Included on this DVD is an ‘extended scenes’ assembly which includes: (1) some more openly sexual dialogue between Joe and Ilsa during one of their bedroom scenes (this is about two minutes in length, and would seem to be the footage cut by the BBFC for the film’s UK release); and (2) an alternate version of the sequence in which Joe ejects Ilsa from his bedsit, presumably intended for use in a stronger ‘continental’ version of the film, where Joe is shown to strip Ilsa naked (an obvious body double is used) as he thrusts her out the door and onto the communal staircase. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track. This track is clean and clear throughout; dialogue is always audible. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Extras include: - Extended scenes (3:48). This is an assembly of footage cut from the UK release by the BBFC in 1963 (some frank sexual dialogue between Joe and Ilsa) and the aforementioned scene in which Joe strips Ilsa naked as he throws her out of his bedsit (most likely a ‘stronger’ insert shot for the cut of the film put together for the continental market, rather than intended for inclusion in the domestic version of the film). - Trailer (1:55). - A gallery of promotional images and artwork (2:29). DVD-ROM extras include: - ABC Film Review article about the film (3 pages, including a colour cover shot of Kathleen Breck as Ilsa); - The Films and Filming review of the film by Robin Bean (1 page); - A Kine Weekly article about the film (2 pages, including a cover shot of Alfred Lynch and Kathleen Breck); - Two pressbooks for the film (6 pages, and 11 pages; the latter of these contains a synopsis for the film in a number of languages).

Overall

West 11 is essentially a film about the circumstances which lead a young man to accept a Faustian pact that is offered to him by a slimy con-man. Although clearly a part of the trend in British cinema towards social realism and the ‘angry young man’ ethos, West 11 has much in common with late-period American films noir. Aside from the expressionistic photography by Otto Heller, the narrative itself could be adapted from a novel by an American author such as David Goodis, Charles Williams or Cornell Woolrich. On the other hand, in its exploration of the dark side of ‘swinging’ London West 11 also has some similarities with Guy Hamilton’s The Party’s Over, released a couple of years later (in 1965; and currently available on an excellent Blu-ray in the BFI’s Flipside label). It’s a fascinating, little-seen film (this seems to be its first DVD release anywhere). Network’s DVD release, containing a superb presentation, is more than welcome and, for fans of this era of British cinema, is definitely worth purchasing. West 11 is essentially a film about the circumstances which lead a young man to accept a Faustian pact that is offered to him by a slimy con-man. Although clearly a part of the trend in British cinema towards social realism and the ‘angry young man’ ethos, West 11 has much in common with late-period American films noir. Aside from the expressionistic photography by Otto Heller, the narrative itself could be adapted from a novel by an American author such as David Goodis, Charles Williams or Cornell Woolrich. On the other hand, in its exploration of the dark side of ‘swinging’ London West 11 also has some similarities with Guy Hamilton’s The Party’s Over, released a couple of years later (in 1965; and currently available on an excellent Blu-ray in the BFI’s Flipside label). It’s a fascinating, little-seen film (this seems to be its first DVD release anywhere). Network’s DVD release, containing a superb presentation, is more than welcome and, for fans of this era of British cinema, is definitely worth purchasing.

References Meikle, Dennis, 1996: A History of Horrors: The Rise and Fall of the House of Hammer. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Spicer, Andrew, 2010: Historical Dictionary of Film Noir. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Williams, Tony, 2004: ‘Wanted for Murder: The Strange Case of Eric Portman’. In: Pomerance, Murray (ed), 2004: Bad: Infamy, Darkness, Evil and Slime on Screen. State University of New York: 157-72 Winner, Michael, 2005: Winner Takes All: A Life of Sorts. London: Robson Books

This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|