|

The Film

52 Pick-Up (John Frankenheimer, 1986) 52 Pick-Up (John Frankenheimer, 1986)

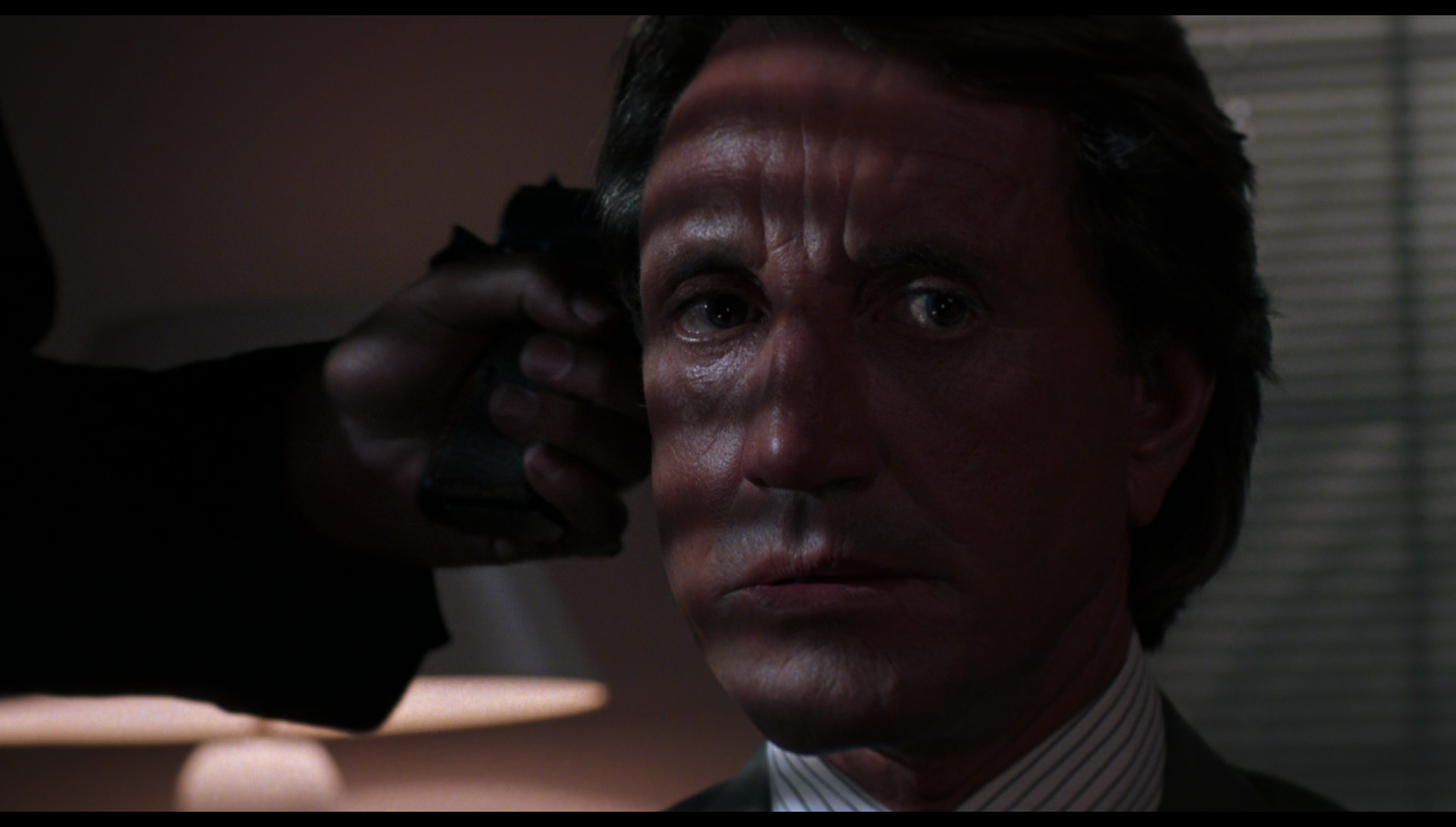

Successful businessman Harry ‘Mitch’ Mitchell (Roy Scheider) runs a company, Ranco Steel, which through a contract to manufacture plating for the space programme has an income of twelve million dollars. Mitch has a distant but respectful relationship with his wife Barbara (Ann-Margret), who has political ambitions. One day, Mitch visits the home of his mistress Cini (Kelly Preston) to break up with her, but finds himself accosted by a couple of thugs who hold a gun to his head and force him to watch home videos taken by Cini, showing Mitch on holiday with his lover when his wife believed him to be at a convention, and video recordings made by the hoods that reveal Cini to be a nude model in a seedy establishment. (Mitch believed her to have a more ‘respectable’ career as a fashion model, it seems.)

The hoods threaten to make the tapes public, thus destroying Mitch’s marriage and impacting upon Barbara’s political aspirations, unless Mitch agrees to paying them $105,000. They then release Mitch. After confessing his role in the affair to Barbara, Mitch decides not to pay his blackmailers, meeting with them but handing them a paper bag filled with worthless bits of paper instead of the money they want. The leader of the blackmailers, porno cinema owner and aspiring porno director Alan Raimy (John Glover), breaks into Mitch’s home and steals Mitch’s coat and gun. Together with his accomplices, convicted murderer Bobby Shy (Clarence Williams III) and the manager of the nude modeling establishment Leo Franks (Robert Trebo), Alan abducts Mitch and takes him to an abandoned warehouse where he shows Mitch another videotape: this tape shows Cini being bound to a chair before Alan shoots her with Mitch’s gun, ensuring the blood spatter hits the coat Alan stole from Mitch’s house.

The hoods demand $105,000 a year from Mitch for the rest of his life, otherwise they will reveal the tape to the police and thus frame him for the murder of Cini. Determined not to be bested by this group of criminals, Mitch visits Leo’s club, where he now knows Cini worked, and speaks with Cini’s friend Doreen (Vanity). Doreen gives Mitch a hint as to the identity of his chief blackmailer, Alan. It doesn’t take Mitch long before he manages to identify Alan and, through him, Leo and Bobby. Mitch approaches Alan directly and, showing Alan his books, proves that he can only get his hands on $52,000. Mitch begins a careful plan to derail the blackmailers, using their own greed to set them against one another. The hoods demand $105,000 a year from Mitch for the rest of his life, otherwise they will reveal the tape to the police and thus frame him for the murder of Cini. Determined not to be bested by this group of criminals, Mitch visits Leo’s club, where he now knows Cini worked, and speaks with Cini’s friend Doreen (Vanity). Doreen gives Mitch a hint as to the identity of his chief blackmailer, Alan. It doesn’t take Mitch long before he manages to identify Alan and, through him, Leo and Bobby. Mitch approaches Alan directly and, showing Alan his books, proves that he can only get his hands on $52,000. Mitch begins a careful plan to derail the blackmailers, using their own greed to set them against one another.

John Frankenheimer’s 52 Pick-Up (1986) was based on a 1974 novel written by Elmore Leonard. The title of Leonard’s novel alludes to Mitch’s handover of $52,000, in exchange for the life of his wife, that takes place towards the climax of the picture, but it’s also a reference to a practical joke involving a deck of cards in which, after asking the player if they want to play a game of ’52 Pick-Up’, the ‘dealer’ throws the fifty-two cards on the floor and tells the player to pick them up. This action may be taken as a metaphor for the destructive impact that Alan, Leo and Bobby have upon Mitch’s life. ‘Guys take over your life just like that’, Mitch tells Barbara late in the film, ‘You never believe anyone can do that. One dumb move and these animals rush in’.

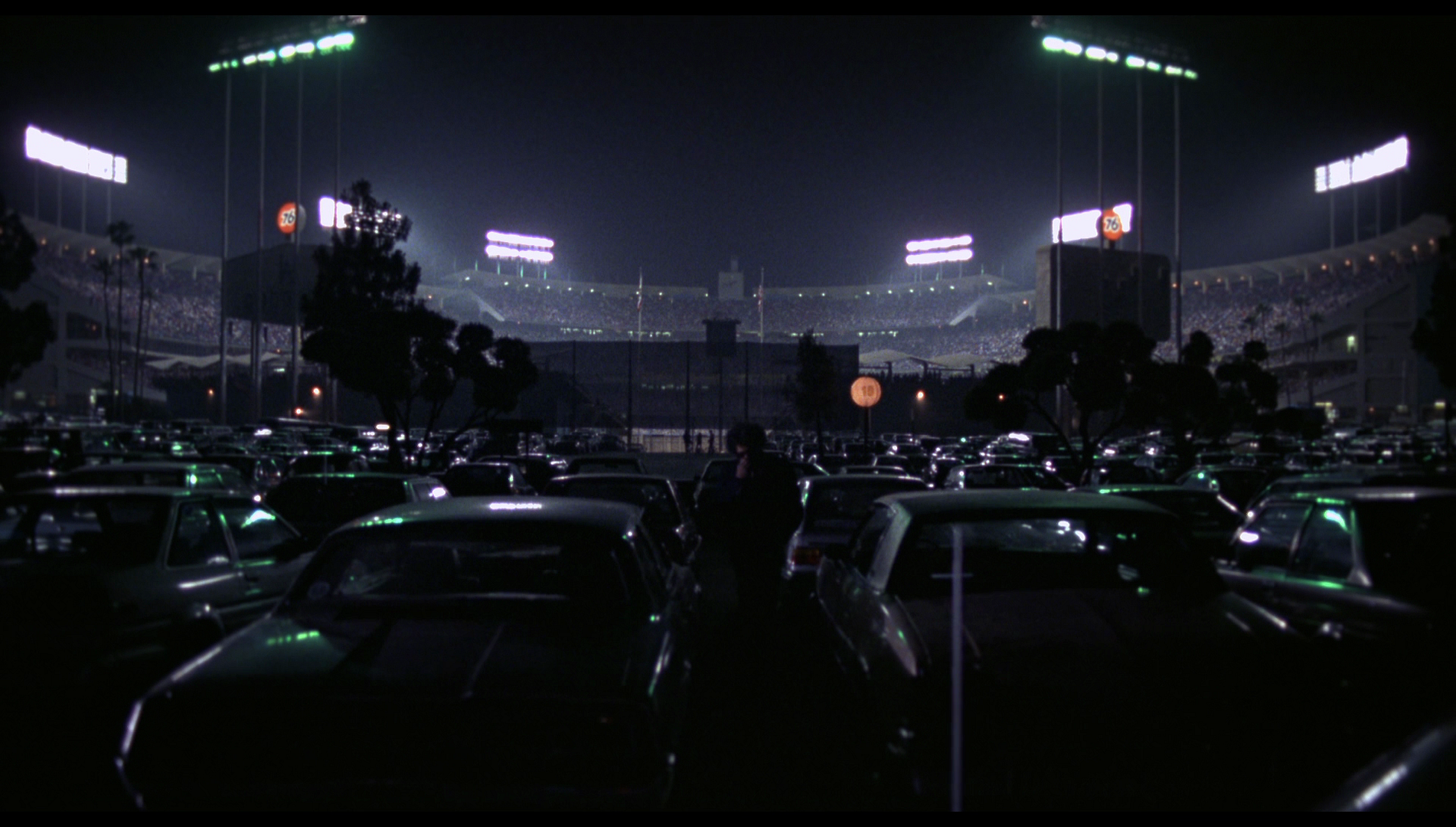

Leonard’s novel was written in the 1970s, during the period in which the author’s work often focused exclusively on the decaying, proletarian city of Detroit. (By contrast, Leonard’s 1980s work, such as 1980’s Gold Coast, often takes sunny Miami as its setting, tapping into the same zeitgeist as Miami Vice, 1984-90.) 52 Pick-Up, the novel, was set in Detroit, and the troubles of that city gave the narrative its backdrop. This film adaptation of Leonard’s book transposes the narrative from the grim ‘Motor City’ to Los Angeles, thus foregrounding Alan’s fascination with filmmaking.

However, Leonard’s story had previously traveled much further afield: the 1984 film The Ambassadors (directed by J Lee Thompson) had functioned as a loose adaptation of 52 Pick-Up which transplanted the story to Israel and wrapped up the blackmail plot in a story about political intrigue and double-cross. That film had been produced for Cannon Films. Impressed with Leonard’s novel after reading it during the production of his previous film The Holcroft Covenant (1985), Frankenheimer discovered that the rights were held by Cannon and lobbied the company for the opportunity to direct a more faithful film adaptation (see Armstrong, 2008: 41). His tactic worked, and Cannon allowed Frankenheimer to go ahead with the picture, though Cannon’s failure to promote the film and poor reviews hindered its commercial success (ibid.). Despite attracting a big enough budget to cast Roy Scheider and Ann-Margret, Frankenheimer was forced to set the picture in Los Angeles owing to the fact that there wasn’t enough money to make the film in Detroit. Stephen Armstrong notes that ‘[t]he changed locale matters little, though, as the L.A. depicted in this picture, despite its sun and palm trees, is as much a moral dead zone as the version of Detroit which shows up in Leonard’s novel: both cities are places where violence proliferates, appearances are at odds with reality and selfishness thrives’ (ibid.: 169). However, Leonard’s story had previously traveled much further afield: the 1984 film The Ambassadors (directed by J Lee Thompson) had functioned as a loose adaptation of 52 Pick-Up which transplanted the story to Israel and wrapped up the blackmail plot in a story about political intrigue and double-cross. That film had been produced for Cannon Films. Impressed with Leonard’s novel after reading it during the production of his previous film The Holcroft Covenant (1985), Frankenheimer discovered that the rights were held by Cannon and lobbied the company for the opportunity to direct a more faithful film adaptation (see Armstrong, 2008: 41). His tactic worked, and Cannon allowed Frankenheimer to go ahead with the picture, though Cannon’s failure to promote the film and poor reviews hindered its commercial success (ibid.). Despite attracting a big enough budget to cast Roy Scheider and Ann-Margret, Frankenheimer was forced to set the picture in Los Angeles owing to the fact that there wasn’t enough money to make the film in Detroit. Stephen Armstrong notes that ‘[t]he changed locale matters little, though, as the L.A. depicted in this picture, despite its sun and palm trees, is as much a moral dead zone as the version of Detroit which shows up in Leonard’s novel: both cities are places where violence proliferates, appearances are at odds with reality and selfishness thrives’ (ibid.: 169).

In its focus on sex, infidelity, blackmail and the femme fatale, Stephen Ambrose has suggested 52 Pick-Up is a ‘neo-noir’ that is comparable to the likes of Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) and The Postman Always Rings Twice (Bob Rafelson, 1981) (Ambrose, op cit.: 170). In terms of its approach to the paradigms of neo-noir cinema, 52 Pick-Up feels similar to Hal Ashby’s 8 Million Ways to Die, released in the same year (1986). Ashby’s film was adapted from a novel by Lawrence Block, a contemporary of Leonard’s whose work has a similarly hardboiled tone to Leonard’s books. Like Frankenheimer’s 52 Pick-Up, Ashby’s 8 Million Ways to Die transplants the action within Block’s source novel (which was set in New York) to Los Angeles. Contemporaneous reviews sometimes highlighted the similarities between these films’ depiction of Los Angeles, David Denby commenting that ‘John Frankenheimer’s 52 Pick-Up joins To Live and Die in L.A. and 8 Million Ways to Die in the flourishing new Los-Angeles-eats-dirt genre. In that city, we are told, life is nasty, brutish and short. Of the three, [Frankenheimer’s film] is perhaps the skuzziest, most squalid, and hopeless. Recommended only to people who enjoy scuzz, squalor, and hoplesssness’ (Denby, 1986: 108).

Stephen Ambrose also suggests that the scene in which Alan and his hoods force Mitch to watch the videotape showing the murder of Cini deliberately echoes the scene in Billy Wilder’s classic film noir Sunset Boulevard (1950) in which Gloria Swanson and William Holden watch her performances in silent films together (Ambrose, op cit.: 170). Certainly, the film’s exploration of the underground world of ‘snuff’ movies and its association with the seedy strip bar Leo manages (and Alan’s aspirations as a porno director) seem very much of-the-time and connect the film to Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979), in which a deeply religious businessman (George C Scott) searches for his missing daughter (Ilah Davis), only to discover that she may be in the hands of a maker of pornographic ‘snuff’ movies. Stephen Ambrose also suggests that the scene in which Alan and his hoods force Mitch to watch the videotape showing the murder of Cini deliberately echoes the scene in Billy Wilder’s classic film noir Sunset Boulevard (1950) in which Gloria Swanson and William Holden watch her performances in silent films together (Ambrose, op cit.: 170). Certainly, the film’s exploration of the underground world of ‘snuff’ movies and its association with the seedy strip bar Leo manages (and Alan’s aspirations as a porno director) seem very much of-the-time and connect the film to Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979), in which a deeply religious businessman (George C Scott) searches for his missing daughter (Ilah Davis), only to discover that she may be in the hands of a maker of pornographic ‘snuff’ movies.

Like Sam Peckinpah’s The Osterman Weekend (1984), which foregrounds the theme of surveillance and voyeurism via the use of videotaped footage, 52 Pick-Up becomes interestingly ‘meta’ in its use of the videotapes and the scenes in which Mitch is forced to sit down and watch, firstly, the recordings showing his and Cini’s holiday before revealing Cini’s work as a nude model and, secondly, the ‘snuff’ movie made by Alan in which Alan shoots Cini. Like films such as Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), in which Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm) records and plays back his murders, these sequences in which characters watch a film-within-the-film focus on a theme of spectatorship. In both scenes, Mitch is a reluctant audience for Alan’s videos. In the first of these scenes, Mitch is held at gunpoint by Alan and forced to watch the video recordings made by Cini and, subsequently, Alan and his gang on the portable television in Cini’s bedroom. Reminding us that we are watching the videotape from the perspective of Mitch, the film features Mitch’s reflection superimposed onto the television screen on which the video footage plays. Throughout, Alan’s monologue draws connections between the video and ‘legitimate’ filmmaking: ‘No talking during the show’, he asserts as the video plays, later commenting ‘Too bad we didn’t have time to score this shit [ie, to write music for it], but we’re working on it’.

In the later sequence in which Alan forces Mitch to watch the videotaped murder of Cini, Alan again provides a running commentary that is almost comparable to the technical commentaries by cast and crew that appeared on roughly contemporaneous LaserDisc releases of films and which proliferated in the DVD/Blu-ray era. ‘Sit down, sport. Second feature, about to start’, Alan tells Mitch as the videotape begins to play. ‘Slick Entertainment Incorporated presents: “Tit in the Wringer”’, Alan quips, ‘Wish we had some popcorn, lemonade or something for you, but… we’re kind of a low-budget production’. As Mitch watches the video, which shows Cini tied to a chair and stripped to the waist before a wooden board is placed in front of her chest, Alan comments: ‘I’m so proud of my lighting. What we’re going to do is give you a reverse angle – I used two cameras for this’, he boasts. When Cini is shot with Mitch’s gun, the bullets striking her through the board tied to her chest, the audience might be forgiven for thinking this is a special effect. ‘The thing that makes Cini a star’, Alan says, ‘is she not only lives the part; she dies it too’. Alan continues, telling Mitch ‘What we want you to see, sport, is that your tit is tight in the wringer. No way to pull it out’. In the later sequence in which Alan forces Mitch to watch the videotaped murder of Cini, Alan again provides a running commentary that is almost comparable to the technical commentaries by cast and crew that appeared on roughly contemporaneous LaserDisc releases of films and which proliferated in the DVD/Blu-ray era. ‘Sit down, sport. Second feature, about to start’, Alan tells Mitch as the videotape begins to play. ‘Slick Entertainment Incorporated presents: “Tit in the Wringer”’, Alan quips, ‘Wish we had some popcorn, lemonade or something for you, but… we’re kind of a low-budget production’. As Mitch watches the video, which shows Cini tied to a chair and stripped to the waist before a wooden board is placed in front of her chest, Alan comments: ‘I’m so proud of my lighting. What we’re going to do is give you a reverse angle – I used two cameras for this’, he boasts. When Cini is shot with Mitch’s gun, the bullets striking her through the board tied to her chest, the audience might be forgiven for thinking this is a special effect. ‘The thing that makes Cini a star’, Alan says, ‘is she not only lives the part; she dies it too’. Alan continues, telling Mitch ‘What we want you to see, sport, is that your tit is tight in the wringer. No way to pull it out’.

52 Pick-Up features the sharp, blackly comic and snappy dialogue that Leonard made his stock-in-trade with the publication of 52 Pick-Up in 1972. When Frankenheimer presented Leonard with a draft of the script prior to production, Leonard was satisfied with it. He said in interview that, ‘Oh yeah, that [Frankenheimer’s adaptation] worked’ (Leonard, quoted in Joyner, 2009: 244). Leonard stated that ‘Frankenheimer sent me a script and he said, “We picked up all of your dialogue from the book”’ (Leonard, quoted in ibid.). Frankenheimer suggested that Leonard could ‘Change anything you want’, but ‘I didn’t touch it. I thought it was fine. And I told him so and he gave me a [screenwriting] credit. Isn’t that something? I didn’t even have to write (the script)’ (Leonard, quoted in ibid.).

Without dialogue, the film’s opening sequence deftly sketches the character of Mitch. The large house and swimming pool tell us he’s successful; he swims before going to work, representing the fact that he’s in shape and physically capable of handling the trials thrown at him as the narrative progresses. Barbara watches on, a look of approval and admiration upon her face; but the couple are emotionally distant, not speaking a word to one another. Driving to work in his Jaguar E-Type, Mitch listens to jazz, suggesting he is something of a non-conformist; and at the plant, he is addressed warmly by his employees, suggesting that he’s a kind and popular boss to work for. Without dialogue, the film’s opening sequence deftly sketches the character of Mitch. The large house and swimming pool tell us he’s successful; he swims before going to work, representing the fact that he’s in shape and physically capable of handling the trials thrown at him as the narrative progresses. Barbara watches on, a look of approval and admiration upon her face; but the couple are emotionally distant, not speaking a word to one another. Driving to work in his Jaguar E-Type, Mitch listens to jazz, suggesting he is something of a non-conformist; and at the plant, he is addressed warmly by his employees, suggesting that he’s a kind and popular boss to work for.

Interestingly, the anti-hero of this piece, Mitch, is a capitalist whilst the villains have a proletarian background. This is to some extent an inversion of the paradigms of noir, in which the anti-heroes are often either downtrodden or representatives of the downtrodden. From the outset, the film presents Mitch as a successful, popular man. Certainly, in the aspirational aspects of Mitch’s lifestyle (the comfortable house, the swimming pool, the nice car), the film feels very much a product of the 1980s. Reflecting on the characters in the film, it’s easy to see in Alan’s gang the archetypes of the Western stories that Elmore Leonard used to write: within the plot of 52 Pick-Up, Alan functions essentially like the ‘brain heavy’ of a Western, the schemer within the gang of outlaws; and Bobby functions as the ‘dog heavy’, the brutal enforcer associated with the outlaw gang and ‘a kicker of dogs who does the brain heavy’s dirty work’ (Roberts, 1995: 130). The principle manner in which Alan’s plan goes awry, however, is in his underestimation of the extent to which Mitch’s ‘tit’ is already ‘in the wringer’ in terms of how heavily Mitch, as a successful businessman, is taxed on his income. At one point, Mitch shows Alan evidence that Mitch pays half his salary in tax to the government. ‘Like a lot of people who make a lot of money, you don’t seem to have any’, Alan says disappointedly. Alan reports back to the others, telling them, ‘The man [Mitch] has no money: the government has him by the balls’.

Mitch’s relationship with Barbara is distant but respectful. Both Mitch and Barbara lead busy lives which intersect only rarely. Barbara watches approvingly as Mitch swims in the pool before work, but even here the couple don’t get the opportunity to talk to one another. It’s only later, after Mitch has been assaulted and threatened by Alan and his hoods, that the lines of communication between Mitch and his wife are opened up. ‘You think perhaps I could book a meeting with you soon?’, Barbara asks Mitch upon his return home, commenting dryly on how difficult it is for each of them to find time for their spouse. Mitch’s relationship with Barbara is distant but respectful. Both Mitch and Barbara lead busy lives which intersect only rarely. Barbara watches approvingly as Mitch swims in the pool before work, but even here the couple don’t get the opportunity to talk to one another. It’s only later, after Mitch has been assaulted and threatened by Alan and his hoods, that the lines of communication between Mitch and his wife are opened up. ‘You think perhaps I could book a meeting with you soon?’, Barbara asks Mitch upon his return home, commenting dryly on how difficult it is for each of them to find time for their spouse.

Seeking something from Cini, Mitch plays away from his marital bed. When Alan, after demanding the $105,000 for Mitch in exchange for the videotape, tells Mitch that he ‘must have rocks in his head’ to allow himself to be ‘caught on film like that’, the audience might find themselves agreeing with him. In a scene shortly after this, Mitch tells a friend about how he came to be involved in the affair with Cini, who he met at a convention. ‘I must have thought I was falling in love’, he reflects, ‘What an asshole!’ Feeling guilt over his betrayal of Barbara, Mitch realises that he can’t go to the police because it will ruin her burgeoning political career: ‘She slept with me all those years while I built this’, he says, referring to Ranco, ‘What am I gonna to do? Am I gonna destroy the one thing she’s built for herself? I can’t do that; I won’t do it’. When he finally makes the decision to tell Barbara about his affair with Cini, Mitch protests that he wasn’t ‘looking’ for an affair but simply stumbled into it: ‘I wasn’t looking’, he says, ‘I didn’t go looking’. ‘She was just a kid’, Mitch asserts, referring to the fact that Cini was in her early twenties. ‘What does that mean?’, Barbara asks, the question echoing with existential potential, ‘Did you play daddy, is that it?’ Finally, the audience is placed in Barbara’s position when she asks Mitch, ‘Do you have any idea how this hurts?’

Despite this, Barbara refuses to abandon her philandering husband, and the film suggests that by reconciling and working as a team they can overcome the threat that Alan and his gang propose to both their lives and their marriage: it’s only by working together that the pair manage to overcome Bobby when he breaks into the Mitchells’ house, Barbara delivering the blow that knocks Bobby unconscious whilst he is fighting with Mitch. Ultimately, the narrative provides Mitch with the opportunity to redeem himself when Alan abducts Barbara, shoots her with heroin and (we are led to believe, though the act isn’t shown onscreen) rapes her, and Mitch concocts a plan to rescue his wife. In many ways, the film’s major theme is the redemption of Mitch; his betrayal of his wife is mirrored in Cini’s betrayal of him. After Mitch has been shown the first videotape by Alan, we see Cini strung out at a sleazy party, conversing with her friend Doreen who tells her that ‘The man [Mitch] was not going to pay your rent forever’ and Cini is ‘better off’ with Alan’s gang. The clear implication is that Cini has betrayed Mitch by providing Alan and his hoods with the means by which they may blackmail Mitch. Despite this, Barbara refuses to abandon her philandering husband, and the film suggests that by reconciling and working as a team they can overcome the threat that Alan and his gang propose to both their lives and their marriage: it’s only by working together that the pair manage to overcome Bobby when he breaks into the Mitchells’ house, Barbara delivering the blow that knocks Bobby unconscious whilst he is fighting with Mitch. Ultimately, the narrative provides Mitch with the opportunity to redeem himself when Alan abducts Barbara, shoots her with heroin and (we are led to believe, though the act isn’t shown onscreen) rapes her, and Mitch concocts a plan to rescue his wife. In many ways, the film’s major theme is the redemption of Mitch; his betrayal of his wife is mirrored in Cini’s betrayal of him. After Mitch has been shown the first videotape by Alan, we see Cini strung out at a sleazy party, conversing with her friend Doreen who tells her that ‘The man [Mitch] was not going to pay your rent forever’ and Cini is ‘better off’ with Alan’s gang. The clear implication is that Cini has betrayed Mitch by providing Alan and his hoods with the means by which they may blackmail Mitch.

Video

52 Pick-Up takes up just under 32b of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 110:16 mins. (The film was cut by the BBFC for its UK cinema release in 1987, and further cuts were applied by the BBFC to the UK VHS release of the same year. The cuts were to the scene in which Mitch is forced to watch the videotaped murder of Cini. These cuts have been waived for UK home video releases of the picture since 2004.) 52 Pick-Up takes up just under 32b of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut, with a running time of 110:16 mins. (The film was cut by the BBFC for its UK cinema release in 1987, and further cuts were applied by the BBFC to the UK VHS release of the same year. The cuts were to the scene in which Mitch is forced to watch the videotaped murder of Cini. These cuts have been waived for UK home video releases of the picture since 2004.)

The presentation here is very good. The image displays a good level of detail and a depth which the original photography strives for: even in low-light situations, the photography aims for a strong depth of field via the frequent use of split dioptre lenses. Colour reproduction seems accurate, with skin tones rendered nicely. The most noticeable improvement over the film’s previous home video releases is in the contrast levels. Previous home video presentations of this film, on VHS and then on DVD, may have given their viewers the impression that the film was shot and lit quite flatly. However, this HD presentation evidences the care and attention put into the film’s lighting scheme: improvements in contrast with this HD presentation give the film a very strong chiaroscuro look, with dark rooms illuminated by shafts of light (a torch; the beam of a 35mm projector, etc). There’s little damage to speak of: a few white flecks and specks are present here and there, and a very faint vertical line can be seen in a small handful of shots. It’s an excellent presentation, a vast improvement over the film’s previous home video releases.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 dual mono track. This is rich and deep, showcasing the film’s bassy main titles sequence. There’s a strong sense of range throughout this track, noticeable when music is featured or gunshots and explosions.

Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and error free.

Extras

The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by critics Glenn Kenny and Doug Brod. Here, the two critics situate 52 Pick-Up within the context of Cannon’s 1980s productions, which oscillated between exploitative action films and highbrow examples of art cinema. They talk about Frankenheimer’s career as a director, and they discuss the differences between the film and Leonard’s novel in terms of the setting, the narrative and the character of Mitch.

- ‘Hardcore Cameos’ (12:10). Here, in a short featurette Glenn Kenny play what Kenny calls ‘spot the porn star’, identifying the cameos in the film of porn actors such as Ron Jeremy, Sharon Mitchell, Amber Lynn and Jamie Gillis (who appear in footage playing on a television monitor), and Cara Lott.

- The film’s original trailer (1:44).

Overall

52 Pick-Up is an interesting film, a neo-noir with a Los Angeles setting that sits alongside Hal Ashby’s 8 Million Ways to Die and William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. Scheider delivers a strong performance as a confident man whose world is undone when Alan and his hoods begin their blackmail plot. Scheider is equally convincing when Mitch decides to turn the tables against Alan, pursuing them and delivering veiled (and, on occasion, not-so-veiled) threats. There’s a fantastic scene in which Mitch visits Alan at the porno cinema that Alan owns. Mitch talks his way into the projection booth; the light from the projector casts a chiaroscuro over the set and actors. Mitch tells Alan that he knows Alan is the man who has been blackmailing him; Alan protests his innocence. ‘You want to play let’s pretend?’, Mitch asks mockingly, before telling Alan, ‘Something about your face makes me want to slap the shit out of it’. 52 Pick-Up is an interesting film, a neo-noir with a Los Angeles setting that sits alongside Hal Ashby’s 8 Million Ways to Die and William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. Scheider delivers a strong performance as a confident man whose world is undone when Alan and his hoods begin their blackmail plot. Scheider is equally convincing when Mitch decides to turn the tables against Alan, pursuing them and delivering veiled (and, on occasion, not-so-veiled) threats. There’s a fantastic scene in which Mitch visits Alan at the porno cinema that Alan owns. Mitch talks his way into the projection booth; the light from the projector casts a chiaroscuro over the set and actors. Mitch tells Alan that he knows Alan is the man who has been blackmailing him; Alan protests his innocence. ‘You want to play let’s pretend?’, Mitch asks mockingly, before telling Alan, ‘Something about your face makes me want to slap the shit out of it’.

Previous home video releases have given the film a rather ‘flat’ aesthetic. The improvements in contrast and detail in this HD release reveal just how carefully shot 52 Pick-Up is, and there’s some wonderful photography throughout the picture. Its ‘meta’ focus on ‘snuff’ films and videotape makes it very much of its era, and at its heart the film is about the redemption of the philandering Mitch.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains a deeply pleasing presentation of the main feature. The featurette identifying the porn actors who make cameos in the film is fairly redundant, but the commentary with Kenny and Brod is enthusiastic and filled with well-researched detail. This is a solid release of an underrated neo-noir picture.

References:

Armstrong, Stephen B, 2008: Pictures About Extremes: The Films of John Frankenheimer. London: McFarland & Company, Inc

Denby, David, 1986: ‘Back from the Future’. In: New York Magazine (8 December, 1986: 106-8

Joyner, C Courtney, 2009: The Westerners: Interviews with Actors, Directors, Writers and Producers. London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Roberts, Randy, 1995: John Wayne, American. University of Nebraska Press

|